Announcements

Hello MUST students!

Considering that Professor Soleil is on sabbatical, and until a substitute professor is appointed, if you have any questions about the course, please direct them to Timothy Walsh.

Lesson 1) First Pioneers Into the World Wide Web

A new year at Hogwarts and a whole new batch of material to study! I hope you all enjoyed your time with me last year, and are ready to delve back to the world with Muggles. I have quite a lot of content to cover, so I hope you are prepared to learn.

I’d like to start the year off by going over our syllabus for the course as well as reminding you of our grading rubric and rules here at MUST.

|

Week One |

History of Computers and the Internet |

|

Week Two |

The World Wide Web |

|

Week Three |

Magic-fying the Muggle World |

|

Week Four |

Muggle Interactions Under the ISoS |

|

Week Five |

Muggle Schooling |

|

Week Six |

Muggle Careers |

|

Week Seven |

Muggle Economy |

|

Week Eight |

Muggle v. Magical Governments |

|

Week Nine |

Muggles and the Wizarding World in Crisis |

And let me remind you of a few basic aspects and rules of the course.

Quizzes that prompt a short answer require you to do so in full sentences. Essays may be answered in a multitude of ways. You may answer the prompt in a traditional written format, but you are also welcome to turn in a creative submission if you’d like. If electing to turn in a creative submission you do not necessarily need to stick to the word count minimum, but the effort put into the submission must be equal to that required to write the number of words that I request in the essay’s prompt. If you are unsure whether your essay submission idea will be accepted, feel free to ask before starting work on it.

Essay Rubric:

50% - Content

40% - Effort

10% - Spelling/Grammar

Automatic 1% for a plagiarized essay, meaning that you will not be allowed to retake it. Also, do not simply copy and paste material straight from the lesson into a short answer or else it will be marked incorrect.

As is the case with all the other classes you’ve taken so far, you do have the option of placing ‘NES’ (Non-English Speaker) or ‘LD’ (Learning Disability) at the beginning of your essays if that applies to you; this will let the grading team know to grade your submissions appropriately.

This Year

The main goal of MUST 301 was to provide you with a brief and varied look at what the everyday life of a Muggle entails -- from their clothing choices to their recreation, all the way to the way they cook and clean. I hope that after learning that Muggles’ lives are not all too dissimilar from our own, you’ve come to have a new appreciation for them and are ready to learn more! This year, I want to focus more on the differences between the Muggle and magical populations, but also how the two interact with one another. In daily life, Muggles and magic users may not always cross, but there are surprising instances in which the two groups actually do, such as within the legal system.

So with that in mind, let’s use today to first discuss one of the fundamental inventions made in the Muggle world, one that we’ve only recently begun to understand. It is so great of an invention that it is the biggest form of separation between the world of Muggles and magic users.

Computers

To get into Mugglekind’s greatest invention to date, we must first start by explaining an earlier invention, called the computer. In the simplest definition, it is an extremely intelligent device that can solve problems (that is, compute them) and process information. At its base, think of it as a machine that can be given raw data and, after some processing time, provide you with results. If you have ever encountered a calculator, you’ll have experienced this system before. In fact, the first computers were invented for the simple task of calculating arithmetic problems and large numbers that are simply too difficult to do by hand. Modern computers do the same thing much faster, and a whole lot more too, and most Muggle homes have at least one personal computer and also a smartphone, which is essentially a pocket-sized computer.

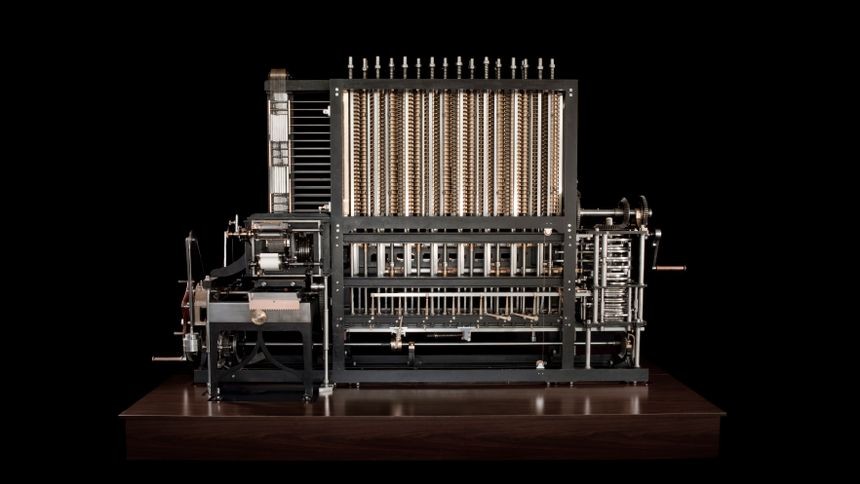

The credited inventor of the first computer was an English man named Charles Babbage, and his invention was referred to as the Difference Engine. Babbage was a mathematician, which is somewhat similar to an arithmancer. This means his life would have revolved around numbers, but instead of looking into magical properties, he would attempt to find numerical formulas that would explain the world around him. For example, we know that items fall to the ground when dropped due to Earth’s gravity (at least you should if you’ve been paying attention in Astronomy class!). A mathematician would use numbers to measure how far the item fell over how much time… and then use the formula relating distance fallen,time taken, and the strength of gravity to find out how strong gravity is. The world of mathematics is incredibly interesting and vast, but should be left for another time. Suffice it to say, Babbage dealt with a great multitude of numbers during his career, which left him in search of a way to navigate them all and preferably without the cloud of potential human error.

As aforementioned, his first invention to solve this numerical problem was the Difference Engine, which he worked on during the 1820s. It worked entirely mechanically; actual parts moved as they crunched numbers to provide an answer for mind-boggling equations. This very first computer would have been absolutely massive, weighing in at an incredible estimated four tons!

But after nearly a decade of work creating this first computer, Babbage found himself in a predicament: his partner pulled out of the project due to its rising cost. The construction of the Difference Engine was promptly halted, and the complete machine was never fully realized while Babbage was alive. The world’s best inventors never give up though, and such was the case with Babbage as well. In 1834, he started working on an upgraded computer that was referred to as the Analytical Engine.

It is at this point in the story that we meet an interesting character: a young Ada Lovelace, only seventeen years old, finds herself at a party and learning about the proposed Analytical Engine. Lovelace had mathematical training, something essentially unheard of for a woman to have in this time period, and began to work out ideas for how the Analytical Engine could be used in a practical manner. In a way, Lovelace became the world’s first computer programmer - a term that is used by Muggles to describe someone who is an expert in computers and knows how to “speak” to them in a language that the machines can understand. It is only with Lovelace’swork and that of other programmers everywhere that anyone can use computers to do anything in their daily life.

Computer Programs and ARPANET

Calculating the results to number problems is only one thing a computer can process, however. As time went by, Muggles began to realize that these machines may be powerful enough to work through tougher problems, but to what extent? Lovelace’s programs taught Muggles in the early nineteenth century that computers could parse through all kinds of information - including numbers, letters, and symbols… but what did it all mean? How could Muggles use this radical technology in order to do something useful?

Many more advances occurred in the years following Babbage’s and Lovelace’s works (feel free to research on your own the careers of Alan Turing, Nikola Tesla, and Vint Cerf!) but for the sake of simplicity, we are going to skip forward in time a bit -- to the 1960s. Groovy!

At this point in history, computers had become much more useful but were still too complicated for the public to enjoy them. For example, early computers made a huge difference in World War II, lending a superhuman mind to British codebreakers’ efforts to read secret German messages. These early computers were also often absolutely massive, needing an entire room to function. They were becoming more powerful and advanced, but it was still difficult to do anything besides simply inputting information and letting the computer produce the output in reply.

This is when a new technique called packet switching comes in. In the early 1960s, an American computer scientist (someone who is an expert in theoretical science about how computers work, not to be confused with a computer programmer) named Paul Baran was tasked with a special project. He was to devise a way that various computers could speak to each other over great distances, specifically in the event of a future war.

The concept he developed was called “packet switching.” The idea behind this term is that you can send over information via a packet, which is a type of data grouping. A packet consists of two parts: a header, which is where text is placed so that the computer may understand what it should do with the information it is receiving, and a payload, which is the large amount of data that the computer can work with. For an analogy, think of it like a parcel you may receive in the post. The package itself is the payload, the actual information that you want the receiving computer to get. But in most mail systems, one’s parcel will have written instructions so that the deliverer knows what to do with it. The instructions may indicate who the package is for, and whether or not it needs special handling. This is similar to the packet’s header, which explains what the computer should do with the following payload of information.

Now that you know the basics of what packet switching is, you may start to wonder how Muggles advanced this technology into something less confusing. Well, with the concept of packet switching now becoming more common among computer scientists, these experts started to develop a separate project that took data sharing between computers into a much broader scale. This early prototype was called ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) and was funded by the United States’ defense system. ARPANET was designed to allow multiple computers to spread information to one another in times of crisis. It used the new technology of packet switching to send over complicated amounts of data over great distances.

This early ARPANET was a great achievement but still needed to be cleaned up a great deal before it could become the easily used World Wide Web that Muggles use regularly today. But I will save that discussion for next time.

And with that, I will dismiss our class. Today’s information was a bit complicated yet it only scratched the surface about what computers and the Internet are. In the next lesson, we will be using this background history to help us understand the Internet of today’s Muggles -- something you will most likely think was magic if you did not learn about the humble beginnings of this technology today!

See you next week!

Anna Soleil

Sources:

https://images.computerhistory.org/babbage/babbage-engine-main.jpg?w=860

https://www.computerhistory.org/babbage/history/

https://www.history.com/news/who-invented-the-internet

**this course has been completely rewritten as of Oct 1**

- MUST-301

Enroll