Announcements

Welcome to Ancient Studies 501!

- If you have any questions about the content or the assignments, please send an owl to myself or one of my PAs. Alternatively, you can write on my profile. Whatever works best for you.

- If you wish to appeal a grade you received, please send me an owl with your grade id so I can have a look and best advise you. If you are unsure where to find your grade id, I can help with that too.

- I will try to have all assignments graded and returned to you no later than a week after submission. Please do not ask for grading updates before then.

- If you see any mistakes, typos or anything like that while you take this class, please let me know so I can fix them.

- You can find my office in the following HiH group: Click here to access Professor Salvatrix's Office. Feel free to join and engage in discussions and various activities related to the ancient world and beyond.

Lesson 6) Celtic Magic and the Power of Books

As the students enter the Ancient Studies classroom, they watch as their professor traces intricate Celtic knotwork patterns in the air with her wand. The images seemingly have no beginning or end. Mesmerized, the students slowly take their seats and stare in rapt attention. The professor coaxes the images to rise up over the heads of the students, and then they slowly fade away.

Amazing, aren’t they? I have to say that Celtic artwork is by far a favourite of mine! Celtic knots have no beginning and no end to them, as you’ve noticed, and, as such, actually represent the mindset of the Celtic people when it comes to their beliefs and therefore their magic.

Today we shall finish our brief foray into the Celtic civilization. I know, I know. I too am disappointed, but there simply is not enough time to cover everything! Let’s have a more detailed look at Celtic magic and the druids today, and then we will look at some fascinating uses of magic by the Celts themselves.

Celtic Magic

Magic use in the Celtic civilization was common practice throughout much of their history. In Britain, magic was termed “awen,” and depicted with the symbol you see to my left. Whereas, in Ireland, it was referred to as “imbas.” Both of these words translate roughly into “force of power,” which I think is a rather appropriate description of magic.

Regardless of what it was called, magic in the Celtic civilization was directly linked to nature and the flow of life. As a people, the Celts strove for harmony with nature and believed that everyone was part of a continuum of creation. They believed that divinity could be found in all aspects of nature. Whether it was trees, rocks, water, or creatures, everything held an aspect of the divine. Trees were regarded as the epitome of the divine, and various areas of the Celtic civilization held different trees as the “highest” or most divine: oak in Gaul (also called Galatia), yew in Britain, and rowan in Ireland.

The way that people used magic in the Celtic civilization stemmed from these beliefs. Druids used rituals to reestablish the balance of nature that had been interfered with, whether through mining, farming, fishing, or other methods. As an example, one of these rituals was the ritual burning of the wicker man, where an effigy was burned as a sacrifice to nature and various gods.

A student flings his hand up in the air with great urgency. “Wait, professor! What about the human sacrifices?” The professor nods with a slight air of resignation.

It seems I can never speak about the Celts without some overeager student asking that question. Very well, here is what we know for sure: we, er… don’t know for sure.

There is evidence that points to the possibility, but much of it is discounted because it came directly from Roman authors, who had a vested interest in making their opponents seem “barbaric” and cruel. There are some archaeological finds that could further support the theory, but ultimately, it’s not clear whether certain human remains found are proof of this practice. If there were indeed humans involved in this ritual burning, celtic beliefs and practices lead us to determine that these practices were very possibly a form of capital punishment for criminals in their society. Granted, it was capital punishment as part of a magical and/or religious ritual, so the line is a blurry one at best. Some sources indicate that if a suitable criminal could not be found for the ritual, someone of high stature - a druid or lord - would volunteer to die as part of the ritual instead.

You see, much like the ancient Egyptians, the Celtic people believed unequivocally that life continued after death. It didn’t matter if someone didn’t pay their debts in this life, they would pay it in the afterlife. It didn’t matter if a lord died as part of a ritual to save the crops from failing, he would simply move on to the afterlife, the next step in the great continuum of life. We simply cannot put our values and beliefs onto these practices, because they are different from our own.

Now, before I get into what types of magic were used and how they were practiced, I would like to remind you about something I mentioned last class and alluded to just a moment ago - there were no written druidic records. To clarify, this is not because they were lost to the ravages of time (as is frequently a consideration when studying any historical society), but instead they were never made in the first place. All of celtic culture, and of druidic magical practices were passed down through oral tradition. Therefore, any written accounts of druidic magic use and beliefs that we use to study them today were written by third parties, and most of these third parties did not actually like the Celts very much. In fact, the most famous account of druidic practices was by Julius Caesar himself. Needless to say, a grain (or more) of salt needs to be taken into account when considering what Caesar had to say about a civilisation he warred with. The rest of the existing sources come mostly from Christian priests who knowingly altered the information to make it fit with Christian theology.

What we can say for certain is that the druids seemed to excel in the areas of divination, herbology (especially for healing), astronomy, and charms.

Druidic Magic

The magic that the druids practiced was referred to by the Greeks as coming from a “natural philosophy.” That is, the druids viewed the word in terms of the natural order, and therefore could see disturbances in the natural order and interpreted those signs as omens. A snow storm out of season, a raven with a white wing, mistletoe growing on oak trees; all of these occurrences were interpreted by the druids in order to prepare for an early winter, a plague, or blight on the crops, and more.

One of the tools that was used for divination by the druids actually falls more under the practice of astronomy. I’m here referring to the Coligny calendar, fragments of which are pictured to my right.

While it’s difficult to glean this from the fragments pictured here, they have been studied extensively. We now know that this specialized, perpetual calendar consisted of a five year rotation of twelve lunar months, plus two “intermediate” months. It was designed as such to make the lengths of the lunar months fit with the solar year of 365 and 1/4 days. It would have taken centuries of astronomical observations to understand, master, and develop this calendar, and it is a grand tribute to the dedication and long-term planning of the druids. While it was certainly used to know when to plant and harvest crops, I’m sure your astronomy professor has told you just how important knowing the phases of the moon is on magical practices. As such, the druids had a major advantage over some of the other civilisations of the time, who did not have this information.

Another advantage the Celts had over other civilisations was the use of druidic magic in battle. In fact, I feel no hesitation in stating that battles during Celtic times, especially those between two or more Celtic factions, were determined not by the prowess of their warriors, but by the magical knowledge and strength of their druids. The greatest of the druids possessed the ability to call forth clouds and mists, bring down showers of fire and blood (at least, according to their enemies), and drive a man insane by tossing an enchanted piece of straw into his face (most likely a precursor to the Imperius and/or Cruciatus Curses).

The Battle of Cúl Dreimhne

One of the most fascinating magical tribal battles (to clarify, by a “tribal battle” I mean a fracas between two tribes of factions of the same culture) in Celtic history is the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne, also known as Cul-Dremne. The battle occurred between the north and south branches of the Ui Neill dynasty. What caused such a deadly conflict between kin? Ownership of a book. Yes, you heard that correctly. Someone wanted a copy of a book, and another person said no. Both the best and worst reason for a battle if I’ve ever heard one! Of course, as with all wars, I’m sure there were other tensions, past conflicts and motivating factors, as well as far more details, but recall that we are working on very limited information due to the lack of written accounts.

What we do know is this. Diarmait (or Dermot), the king of the southern dynasty, called for his head druid, Fraechan, to make a protective magical “aire druad” or a “druid fence” around his army. This was believed to be a sort of impenetrable barrier created from magic. The closest thing we can compare it with would be extraordinarily strong wards -- thinking specifically of the wards and additional spells (like Fianto Duri, Repello Inimicium, and Protego Maxima) cast around the castle at the Battle of Hogwarts. He hoped that his warriors would be able to cast spells and shoot arrows out at their enemies while still protecting all of his men.

It didn’t work. The spell collapsed completely when a northern warrior named Mag Laim made a suicidal dash through the hexed line. His sacrifice destroyed the spell, and the northern army charged. As it took a few moments for the southern army to realize that the spell had collapsed and, coupled with the fact that they hadn’t bothered to wear most of their armour, they were not at all prepared for the onslaught from the northern army. The southern army was thoroughly routed, suffering very heavy casualties, and the northern army triumphed. The now famed Mag Laim was their only casualty of the battle.

So, what can we learn from this historic event? Well, firstly, that magic is not infallible. However, in more generally applicable terms, I’ll quote a common adage. “Don’t put all of your eggs in one basket.” Backup plans, additional strategies, or even simply wearing armor to battle would have significantly improved their odds.

Failed battle strategies aside, druidic magic was certainly impressive at the time and, to give it credit, wards similar to druidic fences are not exactly commonplace today. Sadly, their magic was not strong enough to halt the inevitable annexation by the Roman Empire, but was still enough of a threat that being a druid under Roman rule was punishable by death. This death sentence effectively ended the tradition of druidic magic and its practices. While druids practicing divination and healing continued as late as the fourth century CE in Gaul and the seventh century CE in Ireland and Scotland, the druidic order disappeared, taking most of its magical practices away into the mists.

The Book of Kells

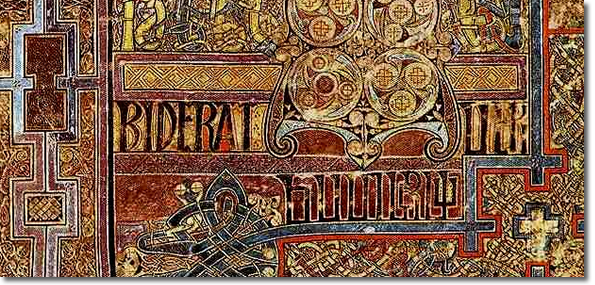

Some of you may be wondering why we are talking about a copy - albeit an incredibly illuminated copy - of the four gospels of the Bible when speaking of the Celtic people. As we know, Christianity and Celtic tradition were frequently at odds. Well, quite simply, many magical scholars believe there is much more to this book than meets the eye. The book itself has survived centuries of raids, thefts, subsequent recoveries, exposure to brutal environmental conditions, and possibly other atrocities that we are unaware of. It is still mostly intact and incredibly beautiful.

How? It is simply not something that happens every day. In fact, most documents that have survived down the ages - religious or not - have been imbued with some sort of magic to keep them safe. Both the location and time when the book was created - around 800 CE in northern Ireland or possibly the island of Iona located off the coast of Scotland - have led many scholars to hypothesize that the book was protected by a descendant of the last members of the druidic order.

If that is indeed the case, and a druid still lived during these times, it is possible that the Book of Kells may have hidden magical knowledge within its pages. Magical scholars have studied the book for ages, and have not found anything concrete. But the mystery still remains, drawing people in.

I suppose we’re tired of hearing so much about books today, yes?

Wonderful! Then you must all be ready for today’s assignments! After all of your hard work on your midterms last class, you will simply have a quiz to complete today. Our next class marks the beginning of our discussion on the Norse. Class dismissed!

Image credits here, here, and here

Original lesson written by Professor Liria Morgan

- ANST-401

Enroll